Remembering the Dead

This is the time of year when we remember the dead. At Hallowe’en, our Celtic ancestors here in Ireland believed the dead and ‘the other world’ became intertwined with the world of the living; Christians celebrate All Saints Day on 1st November, remembering martyrs and the dead; 11th November, Remembrance Day, is the time when we remember those who died in two World Wars.

Remembering the dead is important human trait, with its own rituals, both formal and informal and often very personal. Here we look across our collections at death and remembrance in Clare and see how people were remembered after their deaths in the county.

Robert Keane’s lock of hair is stored in a horn container, with a cork cover.

Robert Keane’s Lock of Hair

This small container carries a lock of hair from Robert Keane of the Beechpark Keane family, brother of the infamous Marcus Keane (1815-83), the man responsible for the evictions around Kilrush and Loop Head during the famine. Robert died in Dublin in December 1873.

During the Victorian period, it was quite common to keep locks of hair of the dead, a practice that spoke to the desire to see death not a permanent thing, but that the loved one might still exist somewhere else, somehow (Lutz, 2010). The Keane’s were Evangelical members of the Church of Ireland (Qunn, 2017), and according to Lutz, the Evangelical revival of the 1830s-40s, and spiritualism’s rise in the 1850s-1860s, all contributed to this “after-death narrative” popularity of retaining locks of hair as a type of relic of the dead (Lutz, 2010).

The lock of hair is held in a container that is mainly constructed of horn but with a silver rim and a cork plug, possibly ivory covered, attached to the base of the lid. It is engraved with the name of Robert Keane of Beechpark House, Ennis and the letter C.H.K, the initials of Charlotte Hickman Keane, Robert’s younger sister.

Robert’s grand-daughter Molly wrote down her mother’s reminiscences of her father life and recorded that before Robert Keane died, his daughter Annie:

‘wept herself to sleep on a cushioned window seat in a room at the back of the house. She awoke to find the room dark and the impression that something had awakened her. Yes, there was, a cry coming from the swampland behind the house, and there she saw the distinctly the form of a woman kneeling, with hair floating out behind her, and as she cried she wrung her hands…the Banshee is wailing for Father’ (Pilkington, 2014)

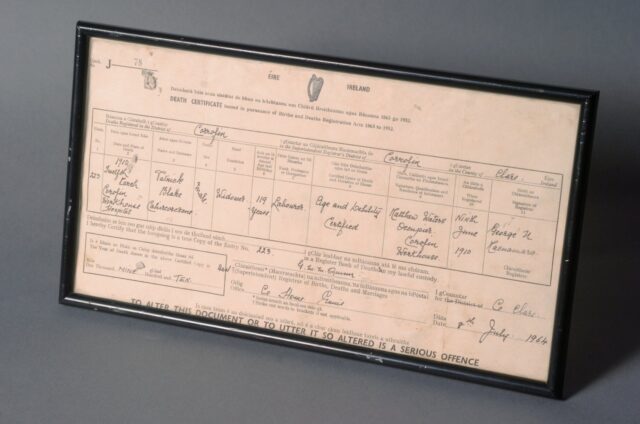

Death Certificate of Patrick Blake

This framed and glazed death certificate is for Patrick Blake from the townland Cahercorcrane near Corofin. According to the certificate, Patrick Blake was a widowed labourer who died in March 1910 in Corofin Workhouse at the ripe old age of 119 years old. While Mr Blake’s advanced age is not supported by the existence of a birth certificate, his alleged age seems to have caught the attention of a registrar, who subsequently framed his death certification It was subsequently hung on a wall in an office in Clare County Council until 2005 when it was sent to the museum.

We checked the 1901 census for Clare, which was available on the Clare Library Website for many years before the National Archives made it and the 1911 census available to the world for the nation as a whole. Here we found a Patrick Blake who lived in Cahercurcaun where he lodged with James Moloney, an ‘Agricultural Shepherd’ and his son Michael. The census showed that Patrick Blake was a widowed, illiterate, agricultural labourer, aged 80 years. It appears, in fact, that Patrick Blake was 89 years old – a very advanced age in 1910 – when he died.

It is not clear why anybody would add thirty years to his age, considering how rare it already was to live to near 90. Following the passing of the Old-Age Pensions Act 1908 which provided 5 shillings a week for those over age 70 whose annual means did not exceed £31 10s, many people added years to their age to get the pension. It can often be seen when comparing ages given by some people between the 1901 and 1911 census’ records. However, Patrick Blake was already qualified for the pension in 1908, so it is unlikely that this was reason for the exaggeration of his age.

The mystery remains!

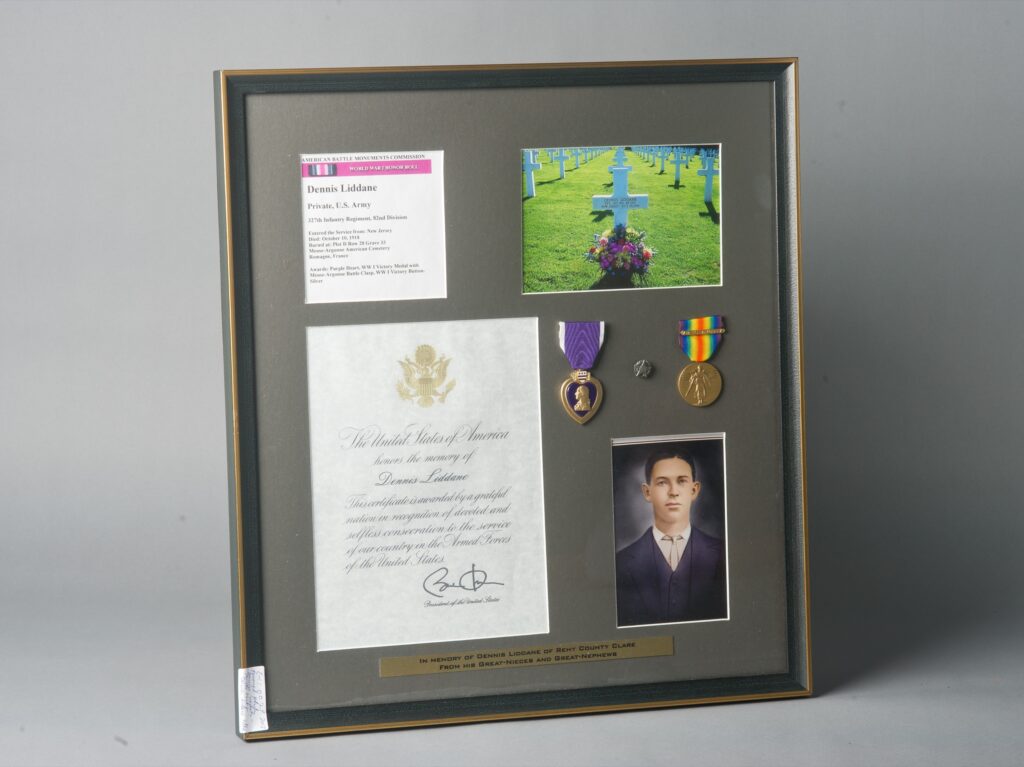

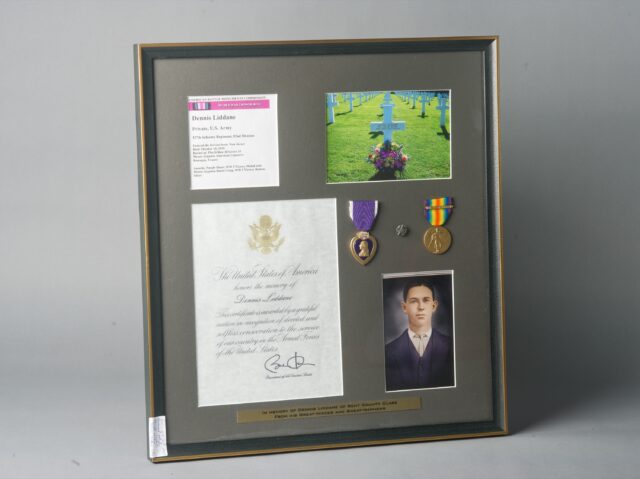

Memorial to Dennis Liddane.

Memorial to Dennis Liddane, US Army

Dennis Liddane was born in 1893 in Rehy, Carrigaholt, Kilkee, the youngest of ten children born to Ellen Pope and Thomas Liddane. His family was evicted from their home in Rehy at the close of the 19th century and moved to Tullig, County Clare. Emigration took its toll on the family and Dennis Liddane’s brothers and sisters left Clare for to both the United States and New Zealand as they grew into adulthood.

In 1911, the census records that Dennis was a 17 year old agricultural labourer, living at home with his elderly parents. He was therefore aged 19 years old when, two years later, he and his brother James emigrated to New Jersey on board the SS Baltic, arriving there on 30th August 1913. He subsequently became an American citizen and on 7th September 1917, following American entry into World War One, Dennis was drafted into the US Army, aged 23 years and 5 months. He was sent to France as part of the American Expeditionary Force and died of wounds received in battle on 10th October 1918.

The memorial contains a colourised photograph of Denis Liddane; a colour photograph of his grave site in France; a Purple Heart medal; a World War One Victory medal with a Meuse-Argonne battle clasp and a citation from President Barrack Obama. It was compiled by Marty Halpin, a great grand nephew of Dennis, and sent to his cousins in Kilkee for presentation to the Clare Museum.

Dennis has subsequently been included on a mobile application for the Meuse-Argonne Cemetery, which tells personal stories of soldiers who are buried in the cemetery and are planning on highlighting Dennis Liddane.

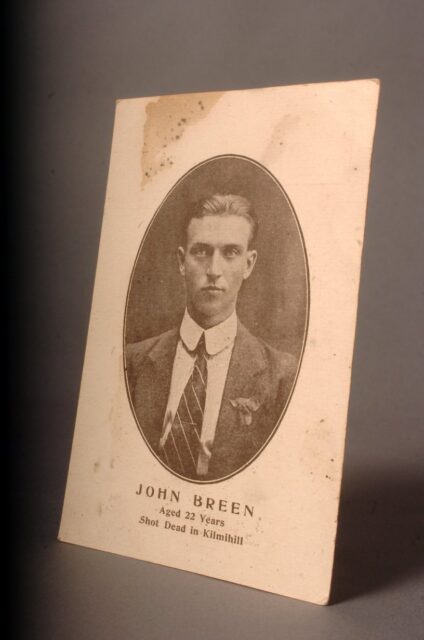

John Breen Memorial Card.

John Breen Memorial Postcard

John Breen was involved in the formation of the Kilmihil Company of the IRA and became one of its first officers. In April 1920 he died when shot through the head during an attack on a patrol of Royal Irish Constabulary. He was aged just 22 years.

Postcards, such as this one, were produced to commemorate the memory of Irish republicans who died in the fight for Irish freedom. This one was found in a house in Kilkee in the early 1960s following the death of a woman who served in Cuman na mBan, the women’s auxiliary of the IRA. Cuman na mBan played an important role in promoting the remembrance of IRA fatalities.

Funerary Crucifix with holy water bottle and candles.

Funerary Crucifix

This was once owned by members of the McKeon family from Ennis. It is typical of a Catholic family of 1950s and 1960s Ireland. The cross contains four candles and holy water inside the cross, behind the crucifix. It would have been used when a person in the home died, as remains were often waked in the family home at that time. Candles were lit, and the local community would come to view the body and sympathise with the family. Prayers were said, windows were opened and mirrors were turned towards the wall as part of the tradition.

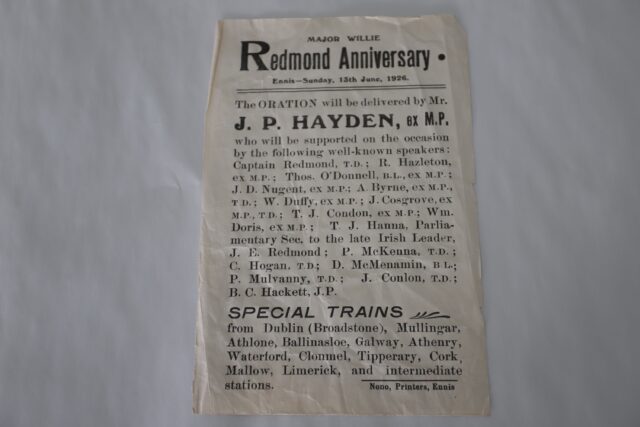

Redmond Anniversary Handbill of 1926.

Redmond Memorial

This document was found among the papers found at the Foresters Club premises in O’Connell St, Ennis in 2004.

The Foresters were mainly supporters of the Irish Party, of which John Redmond MP and Major Willie Redmond MP were significant leaders. Willie was the Member of Parliament for East Clare when he was killed in action on the western front in June 1917. His death resulted in a by-election and his seat was won by Eamon de Valera for Sinn Féin.

His brother, Irish Party leader John Redmond MP died in March 1918 and was buried in Wexford town. The Redmond Memorial Committee was formed to remember the brothers just after the war, culminating the opening of Redmond Park in Wexford in 1931 in honour of Major Willie Redmond. The memorial ceremony for the Redmond’s was held on Sunday 13th June in 1926 at Ennis, close to the anniversary of Willie Redmond’s death.

Here is some film from such a meeting at Wexford in 1925.

The notice was printed locally by Nono printers in Ennis.

References:

Lutz, Deborah (2010) The Dead Still Among Us: Victorian Secular Relics, Hair, Jewelry, and Death Cutlure Cambridge University Press, [Accessed on 5th October 2023]

Pilkington, Kay (2014), Irish family ghosts, Blog, [Accessed on 5th October 2023]

Quinn, James, (2017), Keane,Marcus Dictionary of Irish Biography [Access of 5th October 2023]