What is conservation?

One of the responsibilities a museum in receipt of public funds has toward objects transferred to the collection for the public benefit is to ensure their protection for the future generations to enjoy. Sometimes, that requires remedial conservation.

Remedial conservation is what we call the treatment of artefacts to prevent their further deterioration and can involve cleaning objects or strengthening fragile parts in an effort to make them more stable. Some large museums have a conservation staff member employed full time to carry out this work. At Clare Museum we employ the services of external specialists in different conservation fields when required.

This is the story of a letter that received conservation care in 2022.

The letter

During the Second World War, the celebrated British actor Laurence Olivier directed and starred in a movie called Henry V which was an epic film adaptation of William Shakespeare’s play of the same title. It was filmed in Technicolor in 1943 in neutral Ireland, mainly around Powerscourt in County Wicklow. It was released in 1944, at around the time of the Normandy invasion, and it was intended to boost the morale of the public in the UK.

The film provided the Irish economy with a welcome injection of cash, as hundreds of Irish extras, particularly horsemen, were required for the battle scenes. One of those horsemen, with his own horse, who was employed as an extra, was John McNamara from Clarecastle.

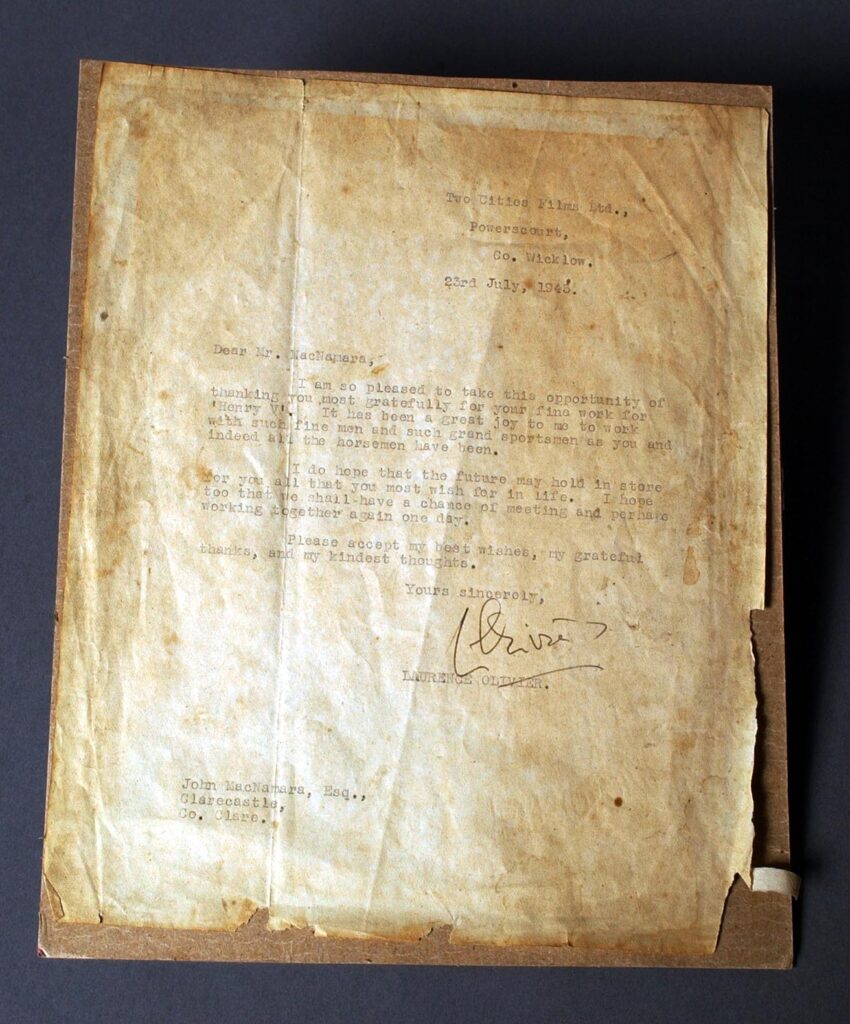

In a typed letter dated 23 July 1943, Olivier thanked Mr McNamara for his work on the feature film. The letter was a treasured artefact in the family and was passed down to his daughter Nora, who donated the letter to the museum collection in 2019.

However, it was clear at the time of donation that the letter would need some conservation work: the surface of the paper was quite dirty from handling over many years while it also had some red ink on the paper, and some tears / wear around the edges.

The typing on the letter also appeared to have faded over the years, though the extent of this could only be guessed. Laurence Olivier’s signature was still clearly visible.

Treatment

In June 2022, Clare Museum sent the letter back to County Wicklow, to Paperworks, Studio for Paper Conservation in Rathnew. It was there that conservator Liz D’Arcy carried out the following treatment:

- Surface cleaned with grated eraser to remove surface dirt

- Reduced soluble discolouration with damp cotton swabs

- Removed the red inscription from the verso* of the paper

- Removed the pressure sensitive tape deposits from the verso of the paper

- Repaired tears and infilled appropriate areas of loss with Japanese paper adhered to the letter with starch paste

- Place in custom mylar sleeve and acid-free folder.

The letter was cleaned to remove the surface dirt that had adhered to the letter over the years. Cleaning also removes insect droppings, accretions, dust or dirt that can build up on paper over time. It was done without damaging any of the historical evidence we wanted to keep, such as the typed text.

Japanese paper, used to repair tears along the edges, is a type of traditional paper invented in Japan from natural fibres and is free of harmful chemicals. It first came to prominence as a tool to be used by conservators following a flood in Florence in 1966. In that instance it was initially used to repair archival documents that had suffered water damage. It is now widely used by conservators in Japan and Europe.

Letter from Laurence Olivier to Mr McNamara of Clarecastle, 1943.

Above is a photograph of the letter before it went for conservation. The dirt on the paper is very evident, while the bottom and the lower right-hand edges are torn and damaged.

Results

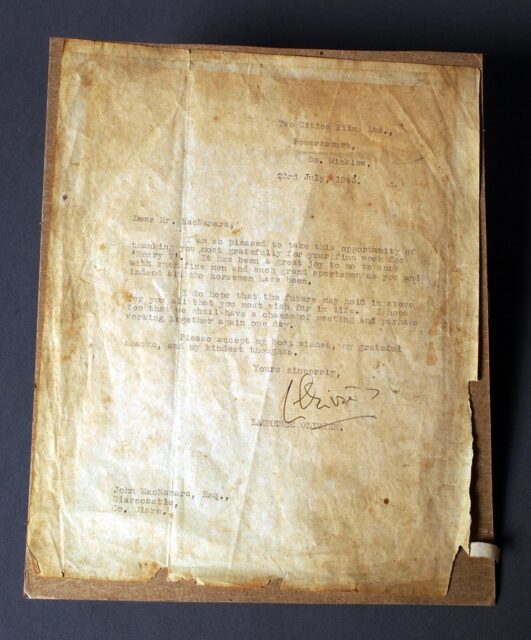

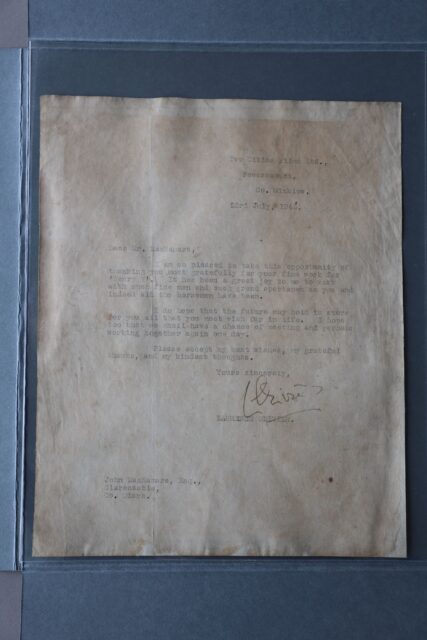

The image below shows how it looks after conservation work by Liz D’Arcy. The conservator did not restore the letter to its original state – that would be restoration – but instead cleaned up the letter and stabilized it. Notice where the Japanese paper was used to replace the worn edges on the bottom and lower right-hand edges.

This photograph will be of use to museum staff in the future when they are spot checking the condition of the letter, as any new signs of deterioration with be evident following comparison with the photograph.

Cleaned letter, inside a see-through Mylar Sleeve for safe handling and display.

Packing and Storage

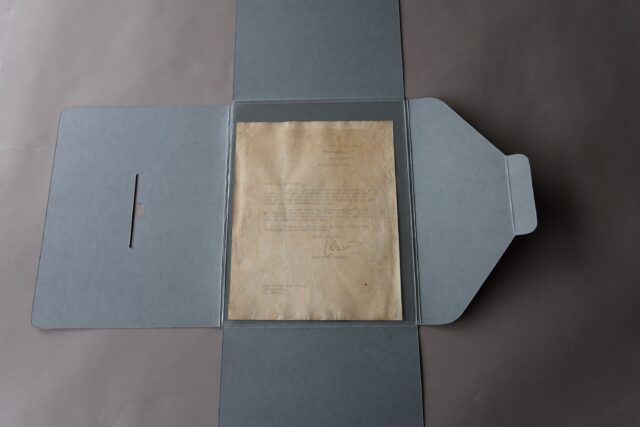

Packing and storage are important in ensuring the care of any artefact in a museum’s reserve collection. In the final photograph, above, we can see the letter in its new Mylar sleeve and acid free folder.

The Mylar sleeve is a ‘see-through’ long-term storage solution for protecting the fragile letter, as it means it can be read, handled and even displayed, if necessary, without risking damage through handling of the letter. It is acid-free, and unlike cheap PVC pockets or sleeves, Mylar does not become brittle, yellow or cloudy and damage the object you want to protect.

Olivier letter in a Mylar sleeve in an acid free folder.

The Mylar sleeve is placed inside an opened acid-free folder. This folder acts as a buffer, and it provides more robust storage protection for the document.

*The verso is the front of the letter.

References:

Masuada, Katsuhiko, (undated), World Wide Spread of Conservation Using Japanese Paper [Accessed 23 May, 2023]

Anonymous, (undated), Why Polyester for archival storage – when is a pocket a sleeve, Preservation Equipment [Accessed, 23 May 2023]