The Object

Tucked away in a quiet corner of Clare Museum is a fountain pen that was used by British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to sign the 1938 Anglo-Irish Agreement. This treaty was an important development between Ireland and the United Kingdom for a number of reasons and saw the return of British naval bases at Castletownbere, Cobh and Lough Swilly to Irish control.

Once the signing had been completed on the 25 April 1938, Chamberlain and Eamon de Valera exchanged pens. The return of these bases assisted the young Irish state in declaring neutrality and staying out of World War Two. While this decision respected the democratic will of the Irish public, neutrality was resented by the Allies from 1940 on. Indeed, it remains controversial to this day. Therefore, the pen was considered to be potentially a ‘provocative object’, if only more people knew about it.

The Question

This important little artefact was often overlooked by visitors, and so it was decided to experiment with its potential as a ‘social object’. This is an approach that holds that all museum objects can be used to encourage dialogue between people, to encourage visitor interaction with each other and the object, and to give the pen more prominence. During the Spring of 2015, a label was added to the outside of the showcase and titled ‘What do you think?’ which explained the controversy, and which asked the question:

What does this pen represent to you?

Underneath this, the visitor was given two options:

-

Is it a tool that made it possible for a small undefended democracy to stay out of the Second World War?

-

Does it represent a betrayal of Britain and the moral failure of the Irish people to defend democracy?

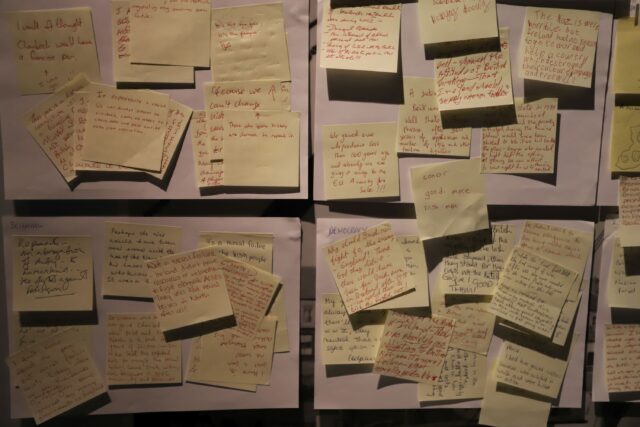

These options set out the two diametrically opposing views relating to Irish neutrality during the war. A post-it pad and pen was provided and visitors were encouraged stick their answers on the low table-like showcase. There is no right answer – depending on your perspective, A or B can be right – indeed, some might feel both are wrong.

Public Reaction

Initially, during the first few weeks, contributors simply wrote A or B on a yellow post-its and stuck it on the showcase with the majority of participants – mostly Irish presumably, as it was the low season for tourists – giving the traditional A answer that might be expected from that quarter. Gradually however, people began to leave little comments along with their chosen letter until very quickly the use of letters ‘A’ or ‘B’ became completely replaced by comments.

The comments indicate that passions were roused by the topic with many varying opinions, some along predictable lines while others were more surprising. A survey of these answers is given below:

Some non-Irish visitors felt that Ireland was correct to remain neutral. Comments included:

I choose A – as an English person, I think if the majority of the Irish State agreed that and [they] stood for their rights [and] not for the British Empire…good for them!

Of course, not everyone agreed that Irish neutrality in World War Two was the correct policy. For some visitors the pen invariably represented Ireland’s betrayal of Britain, democracy or humanity. Examples of such comments included:

The pen represents an abrogation of duty to humankind – the fight against Fascism

Another said:

It’s a moral failure of the Irish people to defend democracy (I’m German)

It is possible that the comment resulted in this response by another visitor, who drew parallels with today’s migrant crisis:

I don’t know about the pen, but moral failure exists today where we see thousands of desperate refugees being ignored by many Governments, e.g. England.

Some visitors were undecided:

Neither – it is a reminder to have an opinion and to question things. War is no solution, but neither is neutrality. Ireland can influence in other ways.

Another can see beyond the pen:

The pen is just a pen. It is the actions of men that count.

One of the most frequent comments made was of course that ‘The pen is mightier than the sword’, frequently accompanied by an actual drawing of a sword. A few contributions were notable because they took no position on the question but instead sought to remind us of the Irish who fought in World War Two.

As one of the comments above indicates, it was perhaps inevitable that the topic was placed in a modern context by some, giving an insight to the current issues playing on people’s minds at that time. Some took the opportunity to make comments such as these three examples:

It shows that one moment [when] the Irish had a backbone and did something to protect the people not their pockets

And

Good on Ireland for remaining neutral. It’s a tragedy that Australians have shown great stupidity in their willingness to be involved in foreign wars.

The latter comment was probably left by an Australian visitor. At this time Australian troops had been fighting in the War on Terror in Iraq and Afghanistan for some years.

Perhaps the rather ordinary appearance of the pen didn’t match up to some people’s expectations considering the significance of the document it was used to sign, as suggested by the following:

I would have thought Chamberlain would have used a fancier pen.

The label asking the question also attracted comments – they were written upon it. Printed on an A-4 size sheet of paper, for months nobody wrote on it, until eventually somebody offended by question A wrote above it

Stop trying to rewrite Irish history, to hell with revisionism.

Conclusion

The experiment was successful in drawing attention to an overlooked object on display in the museum and it was interesting to gauge people reactions to it. It was notable that there was little criticism by visitors to the contributions of others, although visitors could be regularly seen reading responses before posting their own. It was also interesting that although initially encouraged to select A or B as answers, people very quickly used the opportunity to give a personal response sometimes more nuanced or qualified than the questions allowed. This suggests that a more open question might be more suitable when attempting to engage the public with objects in Clare Museum.

Not everyone appreciated this opportunity to think about an object in the museum. I will leave the last word to a lady with a surname common to county Clare, who was not at all impressed:

I think this is all rubbish…you are just trying to make an attraction out of nothing.